Sculptor Lars Fisk has contributed his visionary artistry to Phish's amazing one-band festivals, starting with the Clifford Ball, which set the whole ball rolling back in 1996. Fisk and Vermont builder extraordinaire Russ Bennett have served as co-creative directors of every Phish festival (except for 2009's Festival 8, due to previous commitments). Their responsibility is the visual design of each festival, which involves meetings with band members about possible concepts early in the planning process. In addition to their own hands-on work, Fisk and Bennett hire artists and crews and oversee the projects' implementation. Sometimes the construction continues during the festival, allowing concertgoers to witness art being created in real time and to participate themselves.

Fisk and Bennett have reimagined and reshaped the physical landscape at Phish's festivals, creating intriguing center-area environments that alter conventional frames of reference. For example, at the Great Went (1997), they evoked the look and feel of the city of Rome and its piazzas, while at IT (2003) they engineered "Sunk City," suggesting a decaying urban environment at some distant point in the future.

Fisk and Bennett are presently designing installations and making site preparations for Super Ball IX, Phish's ninth festival, which will be held at Watkins Glen International - a racetrack in upstate New York - over the July 4th weekend. Once again, the artists' imaginations have gone into high gear as they conceptualize a setting that will complement Phish's musical flights. Fisk - who is currently director of the Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City, New York - recently hooked up by phone with Trey Anastasio to take a retrospective look at past Phish festivals and offer a tantalizing taste of what's to come at Super Ball IX. Here is a transcript of their freewheeling, far-ranging conversation.

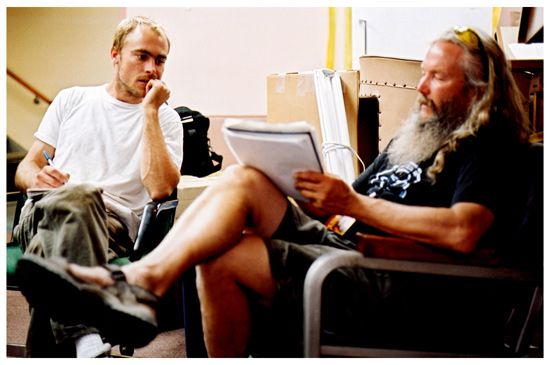

Lars Fisk and Russ Bennett � Phish

Lars Fisk: Hello.

Trey Anastasio: Hey, Lars. Howdy-dowdy. It's your interviewer.

Lars: Wait a minute, who's the interviewee and who's the interviewer?

Trey: I don't really know the answer to that question. Where are you?

Lars: I'm in my shipping container house in Long Island City. it's a house made out of five shipping containers.

Trey: And did you just move in or did you make it?

Lars: It's like these five big whole boxes that I stacked up to make a house.

Trey: Were you able to buy them?

Lars: Well, they were donated from here and there. These are just the standardized containers that they send goods all over the world in. They're all over. So you can get them cheap. And you can stack them up like Legos and cut holes in them and make houses out of them. Pretty nifty.

Trey: . What a cool idea.

Lars: Yeah. So that's where I am.

Trey: I hear you've been going back and forth to Watkins Glen.

Lars: Russ was just there yesterday. I couldn't make it there because we're installing a big sculpture exhibition that opens up on Sunday. Russ is nailing it down up there, and paving the way real nice.

Trey: I'm trying to think back and remember when we first met. You had just graduated from college, right?

Lars: At UVM. The University of Vermont. I was just out of school and boy I just thought I was the cat's pajamas because I got my first solo rental and I felt like I was really moving out into the real world at that time and that was my tiny little studio that just happened to be right across from [Phish management company] Dionysian Productions.

Trey: There was a woman who worked next to you who did an album cover for me, "One Man's Trash."

Lars: Oh, Gerritt Gollner. Oh man, she was such a great artist.

Trey: I remember that you had your studio over there and I remember wandering around and running into her and asking her to do the cover. She did this cool, layered thing.

Lars: I think she's in Berlin now. She's always had her own way of doing things. And she's an incredible artist, really something else.

Trey: So, it's early 1996, and you get this call from Phish, and looking back now, we have to remember that there weren't festivals the way they are now. There wasn't really a roadmap and you get this call from [former Phish manager] John Paluska and he tells you that we're going to do this event and we're going to name it after this guy, this Clifford Ball --would you like to do the art for it? I'm curious about what your thoughts were? I assume that you were shooting from the hip.

Lars: Oh yeah. I mean none of us really had any idea what to expect at all.

Trey: Did you put the first team together?

Lars: Well, yeah. Well, I mean Russ certainly has to be given so much credit for nailing down the whole architectural framework for all of the other creative people that came into that. But when I first started to consider what the hell to do there, I was just a guy in a little quiet studio of his own just tinkering around making little objects which is what sculptors do. They make things. And the way that it was presented to me was that you guys wanted to do a festival that carried out over a few days' time. Time would be an element. Like there would be a duration of a long day where we could do something creative. And so automatically I had to consider creating objects like I had been doing. But over time, and to make the process of making the object interesting also. So what we ended up doing there became kind of a performance of it's own. So I developed a sculpture, a whole number of sculptures that could be produced at that show over the whole weekend and try to make the process of its making be as interesting as the thing itself.

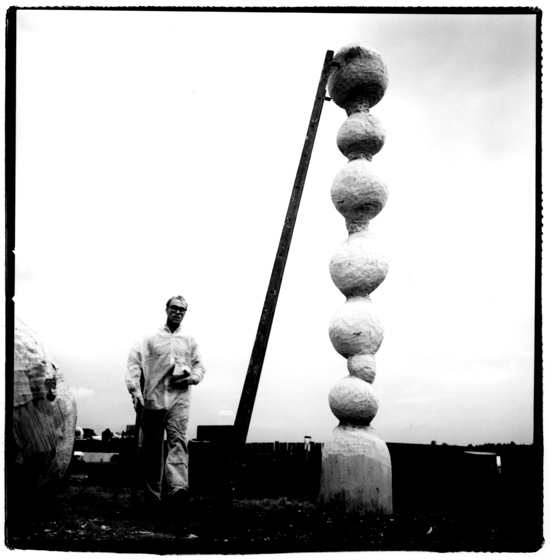

Trey: And where those the balls?

Lars: Yeah. We called them Phish balls, and there was really no direct reference other than the fact that the surface of these things was kind of scaly.

Trey: I remember. And they were carved out of one piece of wood but there was more than one on it.

Lars: Yes, exactly. If you can imagine a wooden totem pole. They were rounded out like a stack of balls, narrowly carved out to complete an independently formed ball. They're stacked vertically like a totem pole. And then the process was that I climbed up there with a hatchet and just chopped them down one by one.

Trey: So was a big part of the idea that it was going to -- I wouldn't say performance art, but that the creative process would happen while the festival was happening?

Lars: Right. Exactly.

Lars at The Clifford Ball. Photo by Danny Clinch � Phish

Trey: I know that your art kind of went down that road for a while, you were doing various balls. You did the tractor balls and all of that stuff. Was that happening before that? Was it a coincidence?

Lars: Yeah, it was kind of coincidental. It was funny because I had just embarked on this whole series which I worked on for over 10 years, actually, this whole series of ball sculptures but that was right at the very beginning. So it's just kind of a funny thing that the Clifford Ball coincided with that.

Trey: And then interestingly, and most people probably don't realize this, but you made a ball for the cover of "Round Room".

Lars: Yeah.

Trey: For those people who are reading this who don't know, it's Lars on the cover. And I also often wonder if people realize that that's just simply a photograph-- that the cover of "Round Room" is the photograph of the sculpture. In this era of Photoshopping people may not realize that's a sculpture.

Lars: Yeah. That's the real thing. It was wooden. It's called the Barn Ball. The Barn Ball was the one that wound up on "Round Room" and it was like a barn, like the quintessential red painted barn in the shape of a ball.. I doubt that people recognized that there is a little figure inside that thing in the picture on the album cover because it's kind of murky and over lit somehow. You can't even really see there's a person in there. The photographer and I were up all night making that image for that. We were just shooting and shooting and shooting. And he had the suggestion that I climb inside there just for the hell of it and then that was one of the shots that ended up being chosen.

Russ Bennett in Ball Square at The Clifford Ball. Photo by Danny Clinch � Phish

Trey: Getting back to the festivals, I think one of the other things that I remember emerging at that Clifford Ball was the concept of a central focal point - we called it Ball Square. Do you remember the conversations that lead to the layout?

Lars: Well, that whole notion of creating like the village model that we use often in these festivals, it comes out of an architectural necessity. So often these festivals have been in wide open areas of nothing. And it almost becomes a challenge of urban planning because all of these people need to know where to go and have a place to go and have a roof over their heads sometimes and shelter and all of the things that a city needs. So it became, all of a sudden as I became more and more involved in these projects, a challenge to design as a planner or an architect, which for me, launched me from thinking about art-making as these little objects to something much larger. Interventions of the landscape and creating buildings for people to move in and around of and whole groups of buildings. And that was a huge challenge and so much fun.

Trey: What were some of the early successes and failures in that regard? For instance, from Clifford Ball, and The Great Went and Lemonwheel -- the first three - was there a steep learning curve? Because I remember the second two seeming to me to be very successful in terms of the central areas where people would gather.

Lars: Yeah. Well, it was really fun for me because I realized the immense scale of these things. And so in thinking about and entering into what to do for the Great Went, for example, we had done Clifford Ball and we knew what we were up against. And so in thinking about the next show for the Great Went I looked to-- actually that I don't know if it ever would come through in a design, what we did, but that design was based on Roman city planning. The Great Went was kind of inspired by Rome and the piazzas of the city.

Trey: I remember the Port-O-Let Piazza, (laughs)

Lars: That's an incredible model, that city, as a design for humanity to be in as an entire city society. So I was looking at the way roads were laid and the way that piazzas punctuated significant points at the end of roads. We were breaking up the whole space of that Loring Air Force Base in kind of the same way and creating subspaces within the larger space in a sort of Roman way of thinking. That's Renaissance Rome.

Trey: Wow. Did you model it specifically?

Lars: Yeah. Actually, that big laundry line was really based directly on the Piazza del Popolo in the Vatican. Michelangelo's big basilica there and then Bernini's big arcade that wraps in a semicircle around the gigantic piazza. You feel like you're inside the loving arms of God when you're standing in this piazza. So those gigantic clothing articles that we had hanging on those ropes, that was based on the Piazza del Popolo, a stretch that I'm sure no one got, but that's what I was looking at.

Trey: But it worked. I'm so glad you're describing this because it worked so well. I'll talk to people who will stop me on the street and we'll reminisce about how powerful those festivals were. I remember taking the golf cart out and wandering around in between sets. And one of the ones that I particularly loved was the sunken neon...

Lars: Oh, the Sunk City.

Trey: That was incredible. At IT.

Lars: That was modeled after like a Vegas, like a Las Vegas 100 years from now or 1,000 years from now, as if the whole city had become like overtaken by nature, again.

Trey: Wow.

Sunk City at IT. Photo by C. Taylor Crothers � Phish

Lars: That was a good one, too, because we collaborated with Mike a bit on that too to produce some of the silly verbiage on those signs.

Trey: On those neon signs. "Yeah is good."

Lars: Yeah is good. That was an instant motto. Yeah is good.

Trey: What was the Lemonwheel concept?

Lars: Well, that one was really outlandish. I think that one may have been my favorite just because it was really far, far reaching. At that point we were going back to Loring Air Force Base, again, for the second year right after Great Went. And what had struck me about being there and trying to create something-- some interesting landscape there, it was so darn flat. And so we took it upon ourselves to try to change that. And we mounded up some miniature mountains in a whole sort of undulating landscape. That was really an effort to make the actual landscape itself more interesting.

Lemonwheel Sticks. Photo by Danny Clinch � Phish

Trey: And then it sort of had an Asian kind of thing to it.

Lars: Yeah. It was modeled after a Chinese garden, There's an amazing Japanese garden at the Montreal Botanical Garden. And this is not a Japanese garden. Japanese gardens are really serene and simple and minimal. Chinese gardens are just crazy. They're really extravagant and colorful with a lot of fantastical elements like waterfalls and miniature mountains and cliffs and architecture pagodas built into this really wild landscape. So it was just so theatrical and that was a real inspiration for what we called the "Garden of Infinite Pleasantries". We had our temples. We had our pagodas. We had our tea houses and our little pond with the illuminated lemon bonsai tree in the middle of this little island. It was really exotic.

Garden of Infinite Pleasantries at Lemonwheel. Photo by C. Taylor Crothers � Phish

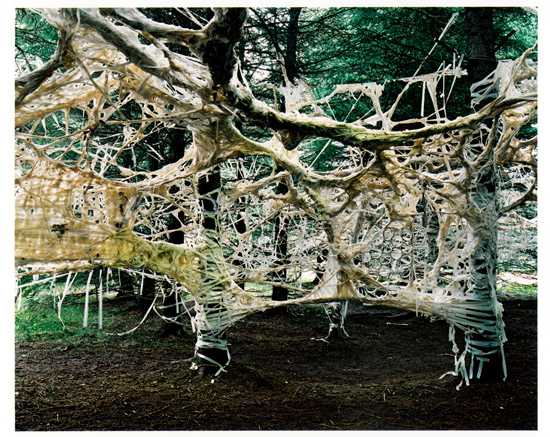

Trey: As memory serves by Lemonwheel, you were collaborating with a number of other artists. Wasn't that the year that the artist who worked with the sticks and whatnot?

Lars: Yeah, Patrick Dougherty.

Trey: Tell me your process - how do you invite an artist like that into the fold?

Lars: Well, yeah, we give them little hints about it. We never want to like fully art director anyone that has their own artistic practice of their own. But, you know, we try to inspire them by creating a substructure or an architectural sort of framework that they can then jump from, that they can enter into thematically in some way. And if they're able to do that, then the whole feel of the entire environment is that much stronger. Someone like Patrick Dougherty, who really doesn't necessarily create works of art that are Asian in any way, but there's some sensibility to using natural materials and weaving and incredible craftsmanship that really supported the whole feeling of this sort of exotic landscape.

Trey: His installation became a bit of a centerpiece the way I remember it. It fit in perfectly.

Lars: It did.

Trey: The other thing that it did was people were invited to walk into it, which is something that I remembered and always liked about the different festivals. That there was often an interconnectedness, a pathway that people were supposed to walk down. At It there was an actual elevated pathway, I think, that went through the sunken city. And you remember that masking tape guy. So you were above him.

Lars: That was John Bisbee, a great artist from Maine who came up with that idea. Yeah, it just became this incredible network, webbing of masking tape. It just got built on by passersby and that was an open invitation for whoever wanted to participate in that project, to get a roll of masking tape and just add to this glom of stuff.

Masking Take Forest at IT. Photo by Bart Stephens � Phish

Trey: I remember driving around with Page after the festival was over and everyone had left and looking at that masking tape sculpture.

Lars: Many of the installations created a cumulative effect over three days. Like the time when we had just plunked down a whole truck load of little stones.

Trey: I've tried to describe that to people, the Rock Garden. I hope you guys do that, again, actually. I would love it if we could do that again at Super Bowl because people were stacking these stones and some of them were tiny.

Lars: It's hard to describe the quality of it because it's just so vast. And the way you get the potency in that sort of sculpture, like with Bisbee's masking tape thing, is through mass participation. So you have who knows thousands of people all contributing to this one thing. It's just incredible what you can make with all of those hands doing a very simple thing.

Trey: After everybody had left the festival site, it looked like the stones that had been dumped had all been used and people had begun stacking these tiny little almost somewhere between miniature little teeny, teeny pebbles. You know, there would be little walls that were made with stacking stones and they would get smaller and smaller and smaller. It's like people started stacking and they couldn't stop. They just kept stacking anything that was around. So it would kind of trail off into these very, very intricate little walls made out of pebbles. It was just amazing. I think John had the idea for that, growing up on the Maine shore with a rocky coastline. It was a great, great idea.

Lars: It was. And the product was amazing. But also the process of that. I mean after a long day and in a dreamy state, what a lovely thing to do with your time but just hunker down with a little pile of rocks and just stack them up. You're thinking about gravity and the material and it's just nature. You're just building something with your two hands and rocks.

Trey: So are there plans for something like that this year?

Lars: Well, yes. Yes, there are. And I think what's going to be kind of special about this event is that it's going to use an energy that we haven't really tried working with before in any of the festivals, I mean a physically manifested energy, a kinetic energy that people-- that other artists and the audience folks can utilize to create stuff. So they can expect to have a whole new energy source at this festival.

Trey: I'm assuming that that was inspired by the location...

Lars: Oh yeah, it was, for sure.

Trey: Because it's a very different space than the other spaces.

Lars: It is. It's got an energy about it. Like Loring or the Seminole farmlands that we saw in Florida, this place has a real character of its own, that's very specific. And that definitely contributed to how we're thinking about our visual design approach here.

Trey: . You just mentioned the Seminoles. I loved Big Cypress.

Lars: Me too.

Trey: I think the initial idea for that was "let's play outside on New Year's Eve" which got a big laugh at first. Okay, you can't do that. It's December 31, come on! And then it wouldn't go away so we were looking at two spots. One of them was going to be the "Big Kahuna" in Hawaii. And then we found Chief Billie from the Seminole Indian Reservation. And my understanding was that our festival team had to go down there six months in advance and cut a field and plant a different kind of grass. My understanding was that there wasn't a proper space. It was really just a swamp.

Lars: Yeah it was. It was the most rugged of all of those venue spaces, for sure. It was pastures with irrigation canals running through. There were no roads. There was really nothing. That was a huge endeavor to transform that into a functioning city.

Trey: I remember it being very spacious and very well thought out. And then there was a round concert area which is strange and unique because it meant that when you were looking-- if you're standing watching the stage, you looked at the wall-- it was hard to get your bearings because normally you're used to being in a rectangular concert space, but that was a conscious decision to keep it organic. And then there was an idea that I remember, which was to make a wall of ice. So like the wall for the concert venue would slowly melt.

Big Cypress. Photo by Danny Clinch � Phish

Lars: That was a big idea for sure.

Trey: I don't think that one happened.

Lars: Well, it got transformed. It ended up being a pyramid. And there were funny stories behind that involved the ice blocks freezing together or an inability to actually get them out of the trucks. I forget exactly what it was. But there was a major problem with these immense ice blocks. So that sort of changed the course of that idea.

Trey: The intent and I remember thinking in the planning stage for Big Cypress, being able to really see clearly, that there was a craft and a skill that was being developed after a number of these festivals had come and gone. Like with the planning of each festival the craft of the whole thing -- it was very cool to be a part of and to watch and think, okay this time we're going to make the venue round. People are going to stay up all night, one of the walls is going to be ice and it's going to melt away over time. And some of it worked and some of it didn't. You guys did the--the decaying city - The Delta.. It was elaborate buildings being taken over by ivy. Tell me about that.

Lars: Well, that was just kind of inspired by the southern cities in the States here that just have a very different feel than the ones that we know up north here. And as a Vermonter I've always just loved the cities like Savannah, Georgia. They call them urban forests where it's a different sensibility to allowing trees and plant life where the nature of that plant life sort of has its way with the built environment. And I was struck by that in my touring of the southern cities of America. We tried to get that same feeling at Big Cypress in that we were in Florida and you get the sense that there's a jungle right there and it's just awaiting its opportunity to grow back over whatever built environment that man has created. So that was the drive behind that.

The Delta Village at Big Cypress. Photo by Danny Clinch � Phish

Trey: And that's sort of tied in with the new millennium.

Lars: Yeah. Thinking about the past and the future and all of that. Sure.

Trey: Right. One of the fun things people probably don't know is that backstage we had built an in-ground pool. I guess it wasn't really "in-ground" but we raised the ground and put the pool in so it looked like it was an in-ground pool.

Lars: The whole experience of being down in the Everglades was just so wild -- so different than anything that we Northerners had experienced. The Visual Design team were staying at Chief Billie's Swamp Safari just down the road from the venue. We were camping out at a safari with all of these wild animals, and grass built huts.

Trey: I know exactly what you're saying. It just looked so unlikely that this thing popped up in the middle of that space. And people kept saying there were alligators if you went two feet into the bush --you've got to watch out for the alligators! And yet, the camping area was so well designed that everybody had almost like their own lawn the way it looked to me. It was a wide space. The traffic was tough getting in, but once you were in it was like Eden or something.

Lars: It was a vast, tropical loveliness.

Trey: And another interesting detail was that it being a sovereign nation there were no police allowed in there. That was my understanding there weren't any. And it didn't matter everybody was incredibly well-behaved and there was no need.

Lars: Well, that was an interesting aspect that we were on an Indian reservation yeah. It was fascinating because a lot of the people that we worked with during that production they were almost entirely Seminole Indians. We would go out with a few of the Seminoles into the jungle to harvest palm fronds --the leaves of a palm tree. And we were instructed on how to harvest these things in a way that the plant could continue growing. We went out in a pickup truck and machete and got all of these palm fronds to build these things they were making for Big Cypress. To be in the company of these Native Americans, it's really so special and to learn their ways and hear their stories. It was like nothing I would ever be able to experience ever again quite like that.

Trey: That's why I always bring it up as such a magical experience. Maybe the fact that it wasn't on a decommissioned air force base and that it was in this community of incredibly welcoming wonderful people it leant it a certain kind of, you know, feeling or vibe or spirit or something. I just remember driving around and it just felt different. It felt peaceful. And Chief Billie kept coming backstage and he was flying over in his plane or whatever it was.

Lars: He was in a helicopter. That was his vehicle of choice. And he was a character that guy.

Trey: And then, of course, we broke down the boundaries a little and we played at a time of day that we had never played before or since, until the sunrise.

Lars: Yeah. And that was one of the things that I wanted to ask you about. That particular night was really the closest that our visual design team has ever been to what you guys do on stage. Because we had that elaborate stage set with the millennium clock, you remember that?

Trey: I do.

Lars: And I was curious to ask you about that how that feels for you--because you guys rarely bring in much by way of visual hoopla aside of course from Kuroda's incredible light show. So how did that feel, having that clock and the Father Time and having to feed him the...

Trey: The sausages? (laughs)

Lars: Yeah.

Meatsick Midnight at Big Cypress. Photo by C. Taylor Crothers � Phish

Trey: It felt great. And that brings me back to conversations with you and Russ and the band members a few weeks ago where I said I'd like to do that more, a lot more. And I know Mike and I talk about it a lot. I think everybody would. I loved intermingling the art and us onstage. And I would encourage more of that. I mean, you know, this year at New Year's Eve we did this Meatstick thing with the dancers. But actually I know there's one Super Ball idea which I won't give away, but to some degree, the stage is going to be intimately linked with the festival grounds.

Lars: Yeah.

Trey: Which I think is incredibly exciting and cool.

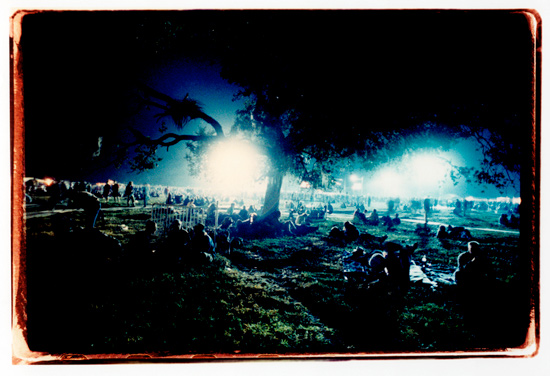

So, Big Cypress was great. Nothing is ever going to match it, I mean, until the next amazing thing happens, I could describe looking out at these people, this audience that I've been staring at for 26 years or something in darkness, right, every night. And people are dancing and they're delirious and they've been up all night. And the sun is starting to come up, oh my god - that was just the most bizarre thing because the sky was all pink.. But it was really just the looks on people's faces, like when suddenly God started to turn on the lights at the end of the party. Oh man.

Lars: Wow, that's a bittersweet thing.

Trey: It was moving to say the least. And then what was really bizarre about it was that we flew home right after the concert and I was standing in my house about three hours after we got off stage. It felt really funny. So more about this year. My understanding is that the site is especially unique.

Lars: It is. Well, yes, it's the race track. It's got some skid marks.

Trey: That should have been the festival title, Skid Marks.

Lars: I saw some incredible skid marks when we first toured the site. We found our way on foot on to the racetrack. You wouldn't ever stand in the middle of a racetrack for obvious reasons. You wouldn't want to do that. But we were standing there and I saw a skid mark on the embankment wall and it made me realize what incredible energy spins around this place. Pedal to the metal baby.

Trey: And I don't know if people are aware of this but it is a NASCAR track and what's cool about it is it's not an oval.

Lars: Yeah. It's got all kinds of twists and turns. And it's a pretty neat space that we have.

Trey: It's more of a Formula One kind of track so I think it's got like 11 or 12 turns and narrow spots. And it's also in the middle of some beautiful mountains. So you've kind of got the curvature of the mountains and the curvature of the track, making a unique geometrical kind of combination that's different than a big swamp and different than a flat rectangular air runway.

Lars: Right. Like a lowering. Yeah, the landscape is just gorgeous. It's beautiful upstate New York. Finger Lakes. It's bucolic and lovely and agricultural and very unspoiled. But then you've got this track set right it the middle of it and it's a really interesting dynamic to think about like NASCAR culture and people that are really into racing cars around in a circle set into this landscape.

Trey: It's pretty far removed from anything.

Lars: It is. When you're getting into that area it's very rural. It's very much a farming landscape. It feels close to home for you and me and it feels like New England. It feels very natural.

Trey: We talked a little bit before about bringing in other artists, as you have over the years. Tell me about your team this year.

Lars: Sure. Well, we've got this ever-changing, ever-growing family of people that we've befriended over the years. And, again, we're going to be calling on a lot of the creative people that we know in Vermont. But as we carry on in life and meet new people and live in different areas of the world, and as we move along we just gather, gather always growing the family. So we're going to have people from Vermont but then some folks from New York City involved and folks from Maine and folks from Connecticut. We had a big think tank session in Vermont last week. We brought in all of the folks that we've been familiar with for a long time and everybody is revved up and coming back to us just now with some really exciting ideas

Trey: How does Independence Day play into your planning?

July 4th, 1999 � Phish

Lars: We've been thinking a lot about America and Americans and the whole history of our young world here. And we're going to play with that a bit. We're going to really be looking at ourselves as Americans.. So it's certainly become a significant aspect to the whole overarching concept to this festival.

Trey: What could be more American than a NASCAR track winding through this bucolic farmland in the mountains!

Lars: Absolutely. The fact that we're in a very significant subculture of America, this NASCAR culture is really kind of fun to think about because for me it's a whole other culture, other than the one that I live in. But it's a really fun thing to goof around with. And think about how something like NASCAR culture, like this group of Americans that are so enthusiastic about this very specific way of life. And how that is just so very different than a lot of aspects of other American culture. We're thinking about place and we're thinking about the time, America, as cultural differences and the Independence Day / Fourth of July as being the birth of America.

Trey: It sounds great. One of my favorite things, probably I think the defining characteristic for me of the Phish festivals that sets them apart for better or for worse than some of the other festivals, is the fact that we only have one band. One day there's three sets, one day there's two, I'm not exactly sure. But to me the quiet time has been the missing piece that's made the art work over the years. What I remember very clearly is when you talked earlier in the interview about the fact that people took part in the rock stacking, the fact that people took part in the masking tape thing and that people took part in the 5K road race. You know, people had time to contemplate these concepts that you've talked about, the Roman concept. I know most of the times these concepts are not obvious and they're not supposed to be obvious but that there's a lot of thought that goes into them and I know because we've had so many conference calls with the four band members and you and Russ, of course, the four of us know what's going on and we're not going to give it away now in this interview, but it's an incredibly cool idea. But the silence and the contrast between concert time and contemplative time is important. And I wanted to ask what your take on that is? That was a long question.

Runaway Jim 5k at IT. Photo by C. Taylor Crothers � Phish

Lars: No. I hear what you're getting at. And I understand that, I mean, we all have a certain capacity for how much we can take in the world of audio, in the world of visual. And, I think, that that's what makes a multimedia event great is to be able to have that space and the frame of mind, the landscape, the soundscape, all of these elements that are contributing to what you are taking in over a weekend and to have some profound moments that are quiet and the profound moments that are really rocking your skeleton. And to have white space between it. And to be able to sort of have the room to digest and take it all in. To be barraged is a difficult thing, but to be able to have these mindsets where you can really intake and enjoy the full depth of what is being presented to you works well when you have it delivered to you in a very careful way. And, I think, that's something that really differentiates these Phish events from the overload of a lot of experiences that one can have these days.

Trey: It brings to mind the impact of Bread and Puppet on these festivals. For those people who don't know, Bread and Puppet is a long-running theater troupe that uses puppetry based in Northern Vermont. For many years, they would hold a pageant every summer on their grounds in Glover, Vermont. Political theater, I guess you would call it. But it's a festival that is a very Vermont kind of thing. And I used to go every year and I'm sure you went.

Lars: Oh yeah.

Trey: And Russ, I guess, used to work on those. And there were unamplified music and theater in a field and it was...quiet. Everyone would sit in silence and the pageant would come over the hill. It would have a theme. And it took, I don't know, 15 minutes for that gigantic puppet show. And it was so moving and so memorable and emotional. And it's those minutes where time becomes kind of irrelevant because of the beauty of this thing that's coming slowly over that hillside. You can see the billowing of the puppets' fabrics and it's a different delivery of experience, where time slows down. It's refreshing in these days when we are barraged with advertisements and the pace of movies and television and the internet. It's very different to slow it down.

Lars: Yeah.

Trey: Russ Bennett has been known to quote a mantra of Peter Schumann, who's the main guy at Bread and Puppet. He would say, "Slower, slower, slower, less." And that is so rare, exactly what you're saying. Everything is so fast and so you're just bombarded with information. And I think back to that moment that I described at Big Cypress where you really felt like you were away from life. It felt like an escape. The Phish festivals often feel like that to me, like some kind of tranquil La-La Land. I remember hanging around by the flatbread pizza oven at Lemonwheel or the Great Went just talking to people, just sitting on the golf cart and hanging out. And I think if there had been band number 17 was on the stage going boom, boom, boom, you wouldn't have that. You'd never have that moment. And think about how profound your experience was just walking on the track or next to the track before we even set up the festival. Just being in that space was incredibly cool. So I just wanted to touch on that because to me it's such an important part of the planning of these festivals.

Lars: In our business we call that the white space. In the visual art world you have that white space which just operates as meditative space. It's non-space. That's important.

Trey: Right. Very.

Trey on the tarmac at The Clifford Ball. Photo by Danny Clinch � Phish